This article originally appeared on PARKLU.

What does the future hold for China’s KOL industry after COVID-19? Influencer marketing has been one of the defining success stories of the past decade in marketing around the world. In China alone, one 2018 report placed the value of the KOL marketing industry at over RMB 100 billion, and the sector has only matured and expanded since then. However, not all brands are convinced that KOL marketing is the way to go. And as the Covid-19 has forced companies to scale back their marketing spend, particularly in Western markets, many brands have simply been unable to commit to the kind of big-budget KOL campaigns that they have invested in over the past few years. And we’re not talking scrappy, cash-strapped startups—major brands have all been cutting their influencer spending. So what alternative tactics are working for these brands, and does their apparent success cast doubt on the prospects for China’s KOL industry after COVID-19?

Seeking out micro-KOLs and brands’ own livestream

According to MCN Digital Brand Architects, brands cancelled around 30 percent of the content collaborations they had booked with the agency’s influencers in the month of April alone.

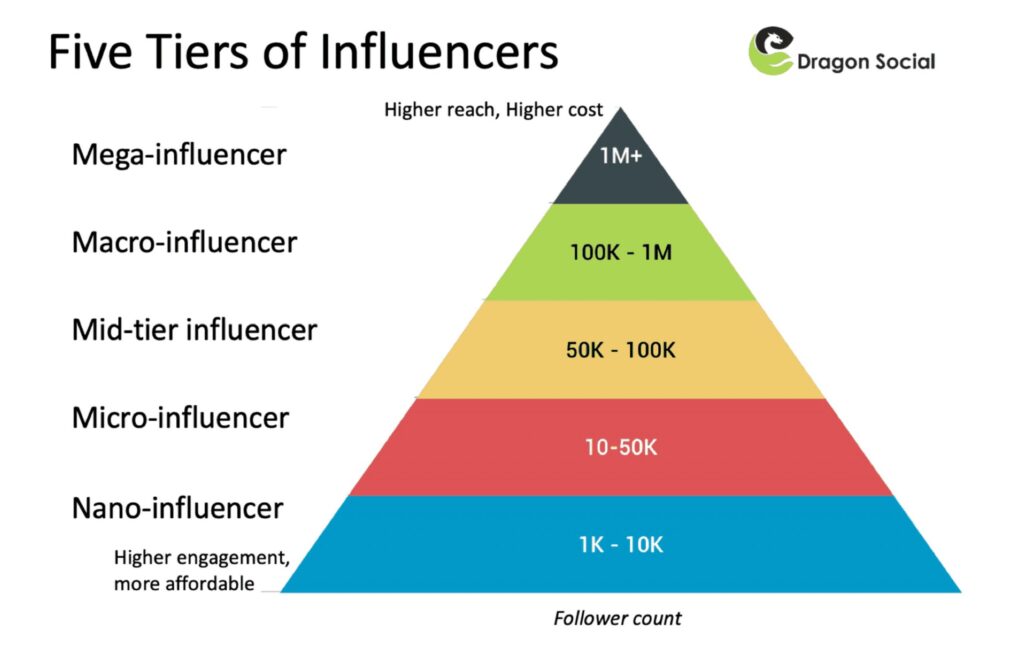

Brands like swimwear label Andie have switched their attention to micro-KOLs and micro-influencers. The mechanics of working with micro-influencers are similar to any KOL campaign. The brand uses the power of endorsements to tap into the influencer’s fan base. The difference is that the brand is typically not paying a fee to the micro-influencer (or to an agency), but rather sending products and samples to these influencers in return for a mention. Obviously, micro-influencers don’t have the reach of a star KOL—this category of influencer usually has a fanbase numbering in the very low thousands. However, micro-influencers tend to be followed by fewer bot accounts, meaning the brand can enjoy more genuine engagement with followers. Micro-influencers also tend to have a more personalized relationship with their fans than a mega-KOL can possibly sustain. The result is that working with a spread of micro-influencers can yield great results for the brand.

Figuring out which Chinese influencers to partner with is often the first step. Source: Dragon Social

Many brands have also opted to forge their own path without any help from influencers large or small. The economic and social fallout from the pandemic prompted a surge in the number of brands that decided to launch their own live streams. Though lacking the star power of a big-name KOL, brands like beauty label Forest Cabin and department store InTime racked up remarkable sales figures in China. In many cases, these brands used their live streams as a digital replica for the in-store experience—even training sales assistants to become Livestream hosts. Research from Mintel showed that Chinese live stream viewers were about as likely to trust a sales associate’s recommendations as they would a KOL’s.

China’s KOL industry after COVID-19: Authenticity matters

Pandemic cuts are not the only factor that might move brands away from KOL marketing. There’s been some reporting to suggest that younger consumers are experiencing “influencer fatigue.” Adina-Laura Achim wrote about this phenomenon for Jing Daily in December 2019, noting that “buyers have become increasingly exhausted by KOLs and influencers and are turning away from them”. Influencers originally appealed to brands because they offered a refreshing contrast with traditional celebrity endorsements and were seen by consumers as authentic voices. The argument is that over time influencers have become indistinguishable from celebrities, and with the inevitable buildup of scandals and controversies involving KOLs, consumers have become skeptical of the influencer industry.

The critique of China’s KOL industry after COVID-19 is rooted in a search for authenticity that continues to drive consumer behaviour. Consumers still want to learn about and gain recommendations on products and services, but they may have grown disillusioned with putting faith in KOLs as trusted messengers. This development has two upshots. One, consumers may trust themselves to circumvent the influencers and seek out an authentic perspective direct from the brand’s own voice. Secondly, consumers will still look to people they know—friends, family, and acquaintances—for recommendations and suggestions.

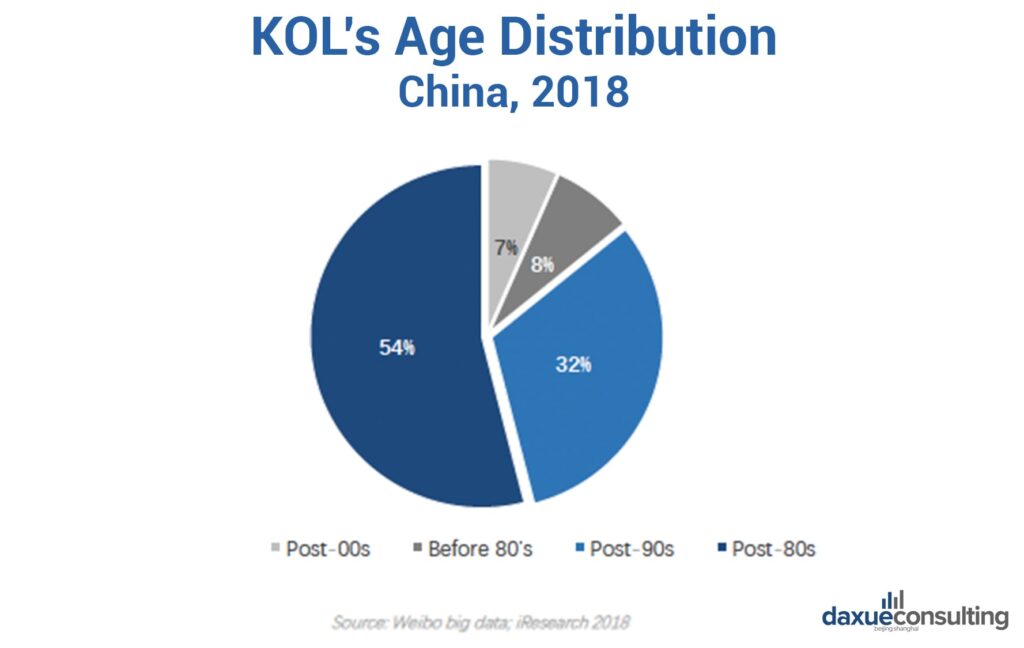

In 2018, more than 50 per cent of the Chinese KOLs were born in the 80’s. Data source: Weibo, iResearch, Daxue Consulting Analysis

That’s actually a double opportunity for brands. Firstly, brands can lean into developing their own content to try to present an authentic face to the consumer. Menswear brand Bonobos is one brand that has done just that since the pandemic hit. Bonobos moved away from collaborations with high-profile celebrities, choosing instead to double down on email marketing, with an emphasis on light-hearted and shareable content.

While consumers will form their own communities with people they are close to, brands can also create spaces where like-minded consumers can forge, if not friendships, then at least a sense of community. This paves the way for these brand-owned spaces to become dynamic hubs where consumers can mutually influence each other, and where user-generated content can flourish, perhaps leading to some members becoming micro-influencers within the community itself.

They may be able to save on influencer fees, as well as fees paid to MCNs—which can multiply beyond the brand’s expectation in the Chinese context. Learning to communicate more authentically and building brand communities are both best practices for the modern marketing operation, both in China and elsewhere around the world.

KOL marketing in China is indispensable for brands

These are all important tactics for marketers in China, however, marketers should be wary of abandoning KOL marketing entirely. In fact, KOL marketing in China is indispensable for brands, particularly in the post-Covid world. By their nature, these initiatives are difficult to scale. Brand-owned communities are supposed to be exclusive to a tightly defined group of consumers, and therefore, there’s a natural upper to the number of consumers a brand will be able to reach via its own community. Brands who turn away from KOL marketing are closing themselves off to the broader demographic that can be reached via an effective KOL campaign, not to mention viral potential.

There’s no doubt that China’s KOL industry after COVID-19 will continue to evolve in China and in the West. However, KOL collaborations will remain an indispensable part of how brands will market to Chinese consumers. The transformative impact of COVID-19 may be more pronounced in Western markets, thanks to the prolonged encounter many European countries have had with the pandemic in contrast with that of China—but even that is showing signs of turning around.