The onset of remote and hybrid work in the museum sector hasn’t just changed the use of workplace technology — it has also required workers to pay more attention to the communication preferences and schedules of colleagues.

“I had to think it through,” says Annelisa Stephan, Assistant Director, Digital Content Strategy and UX Design, at the J. Paul Getty Trust, with over 1,000 people on staff. “Does my own mental model work for others?”

Even in a relatively new workplace like the First Americans Museum, Adrienne Lalli Hills has observed preferences that favor one form of communication over another. Image: First Americans Museum

Adrienne Lalli Hills, Director of Learning and Community Engagement, First Americans Museum, in Oklahoma City, says that at her smaller institution with about 30 full-time staff, people were generally respectful of the communication preferences of colleagues, but it takes work. “I have tried to communicate to others that, ‘Hey, I’m a weirdo. I will be emailing you late at night. Please don’t take that as a sign of urgency.’”

At her medium-sized institution of over 500 employees, Sheeza Sarfraz, Publishing Manager and Editorial Director at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, says that Outlook emails are still the most common (and important) communication format, followed by chats and calls in Teams, comments on documents and presentations in Microsoft’s Sharepoint and OneDrive, and finally, texts and phone calls, now often reserved for more pressing matters where an urgent response is required.

Because of colleagues’ staggered schedules, Stephan adds, video meetings have become the default, but the tendency to add more meetings just because they don’t require physical movement is hard to resist. “Standing group meetings beyond three to four people are more difficult virtually, so I canceled all of them and started from scratch.” Stephan tries to be respectful by avoiding “days of back-to-back Zoom meetings.”

Hills says that different parts of even her smaller institution do favor one form of communication over another. “Some people are exclusive to email or texting,” so one has to be intentional with trying to talk to them in person, she says. “You get these little eddies within the institution that have varying levels of familiarity with each platform,” even in a relatively new museum (it opened in September of 2021).

Increased adaptation through hybridity

Early on during lockdowns, the Royal Ontario Museum developed a remote-work toolkit, says Sheeza Sarfraz, to ensure employees remained connected digitally. Image: Royal Ontario Museum on Facebook

Sarfraz says that COVID-driven remote and hybrid work did require increased adaptation and familiarity. “The pandemic accelerated our use of organizational tools more comfortably across the board. In the before times, the use of file-sharing software would vary by department or project, but during the pandemic, Teams and OneDrive became ubiquitous.”

Digital communication has positives and negatives. Sarfraz says, “It’s harder to connect with people virtually, especially in a large meeting. The level of interaction is definitely more forced, especially when you can’t really see everyone in the digital room. As an organization, we developed a remote-work toolkit early on to ensure that people weren’t feeling isolated or disconnected. Still, there’s a different level of camaraderie when you’re seeing people in person instead of as a square on your screen.”

One upside of increased remote and hybrid work, Hills notes, is that “we have to work so hard to achieve clear communication and a shared understanding, whether that’s through more conscious note-taking, sharing, and creating institutional documents” for review by multiple people. “I feel like it also levels the playing field for people who don’t have access to the sidebar hallway conversations.”

Sarfraz agrees. “There were challenges in the beginning, but that ultimately put the onus on us to start sharing information and updates more openly and widely — either formally through regular cross-departmental check-ins and emails or informally on group chats.”

Aligning digital and emotional skills

With work-from-home arrangements in place, “there was no choice but to switch to flex hours, which led to a greater appreciation of each other’s availability,” says Annelisa Stephan. Image: © 2005 Richard Ross, courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust

“The pandemic also reset expectations about responding right away,” notes Stephan. “People learned to prioritize and not jump at every incoming email; they are aware of the high volume of communication, so they’ve created systems that work for them.”

Even for her digital department, running the technology and facilitating the human connections within meetings are difficult to do simultaneously. There is an interesting alignment between digital and emotional skills, she notes. “Usually the person who sets [the Slack channel up] ‘adopts the puppy.’”

She adds that these distributed tools can also increase inclusivity for early-career staff. “Many have ‘digital emotional literacy,’” she notes. “They show up emotionally.” Experience with social media can “inform an informal way of communicating. It’s a hugely valuable skill in digital workplaces.”

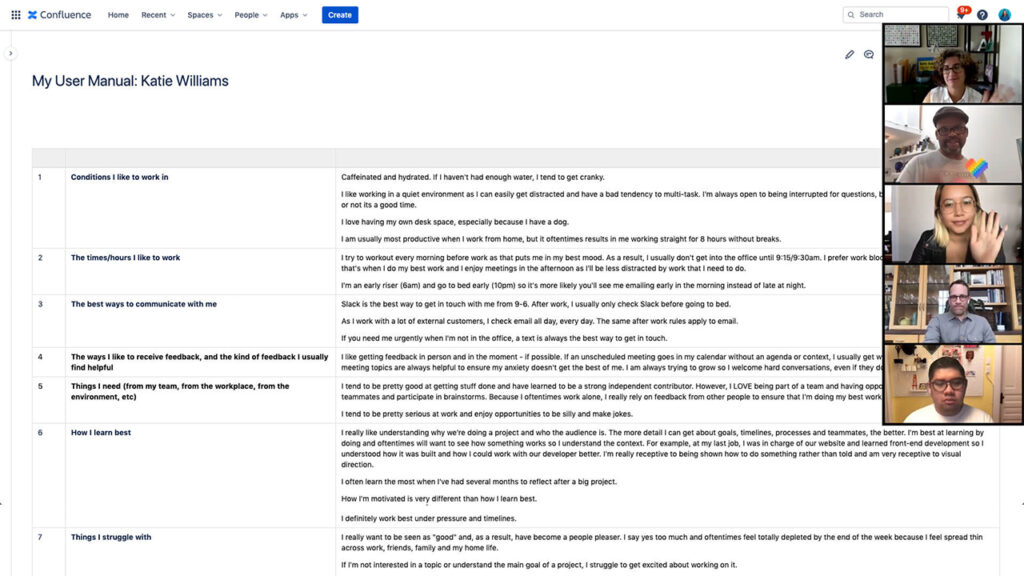

Atlassian’s My User Manual template asks team members to list their communication preferences to encourage more effective online communication. Image: Atlassian

Hills notes that she would like to see institutions invest in staff training in the skills that make these practices possible. “We need coordinators and project managers, people who really enforce and reinforce the agreed-upon methods of communication and documentation. I think it speaks to the very important work of administrative and coordinator colleagues.”

Sarfraz says respecting others’ communication preferences and schedules was a promising new practice. “Working from home was an adjustment, especially for those with children or other dependents. There was no choice but to switch to flex hours, which led to a greater appreciation of each other’s availability. We were able to comfortably share our working hours and indicate a preference for how we could be reached — over email, chat, text, or phone. It shouldn’t have taken a pandemic to introduce or acclimate ourselves to a better work-life balance.”

It remains to be seen if museums will take on profound communication preference guides more common to tech organizations, such as Atlassian’s My User Manual or GitLab’s personal readme files. Meanwhile, Stephan hopes and believes that some of this change will be permanent. “Choice is respected. People were able to explore and become adept with digital tools. These are things that we’d wanted to implement for years.”

Robert J Weisberg has been working in the publications and technology part of the museum field for over a quarter-century. Read his twice-weekly writing about the organizational culture of cultural organizations by subscribing for free to his blog Museum Human. He can also be found on Twitter at @robertjweisberg.