The concept of the gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, has been a central tenet of immersive curation since its emergence in 1827, inspiring generations of collaborators to take on the white cube through a collective lens. Over the past decade, spurred by a new wave of “edutainment”-based programming and applicable digital innovations, museums have experienced a rise in what could be termed the gesamtkunst-show, sense-immersive exhibitions that engage the viewer in more ways than the visual. Multi-sensory engineering urges institutions to borrow from the UX approaches of Silicon Valley as they center experience-oriented design principles — in other words, museums are taking notes from the tech sector, and those notes are sometimes perfumed.

The history of scent in museum spaces is not a particularly long one. In 1984, curators at the Jorvik Viking Centre in York, England recreated the village stink of an ancient Viking city through a series of scratch-and-sniff cards; a 1999 exhibition on food at the Hamburg Speicherstadtmuseum piped the scent of sugar, beer, and wine through a ceiling tube.

Following a landmark study examining the link between smell and nostalgic memories in 2009, however, curators and exhibition designers started to take the integrative powers of olfaction more seriously. The Art of Scent, 1889-2012, at the Museum of Art and Design in New York was the first major exhibition to recognize scent not just as an interactive tool, but an artistic medium unto itself. Curated by eminent perfume critic Chandler Burr, the show tracked the evolution of aesthetics in the medium, allowing visitors to unlock new dimensions of interaction through synthetic ingredients. The installation, designed by acclaimed architectural firm Diller, Scofidio + Renfro, introduced an interactive salon to those in attendance, further illustrating the relationship between scent and design.

The Art of Scent’s exhibition space was punctuated by a series of twelve sculpted wall alcoves, which, as visitors leaned in, triggered the release of a scented stream of air. Image: Diller, Scofidio + Renfro

“Perfume is an art, of course,” notes Burr. “As Picasso said, ‘Art is completely artificial.’ There is no work of art created by nature; art is created by the mind. So is scent a medium in which great works of art can be created? Emphatically yes. Works of fragrance can absolutely help inform an audience’s point of view. Works of fragrance deserve exhibitions about them.”

Today, the Mauritshuis Museum in the Hague is doing just that — putting the nose front and center. Its latest exhibition, Smell the Art: Fleeting — Scents in Colour, open to the public in accordance with the country’s COVID regulations in late May, encourages viewers to “smell the 17th century” in all its pungent glory. Alongside 50 historical artworks from their collection, visitors will have the opportunity to experience eight smells that help the paintings’ subjects, ranging from parties to autopsies, come to life in the gallery.

“We worked with perfumers at the International Flavors & Fragrances, who produced the smells for us,” curator Ariane van Suchtelen tells Jing Culture & Commerce. “The smells have different sources — one goes with a cityscape, for instance, another smell has to do with the bleaching of textiles, and three of the smells use historical recipes to create a sensorial experience for the viewer.” The physical curation of scent, especially in the age of COVID-19, required a specific deployment of perfume within a space. “The dispensing is dry dispensation, so not actually a liquid,” explains van Suchtelen. “Visitors can use a Coronavirus-proof foot pedal to release just a few molecules. We didn’t want all the smells to mix in the air of the galleries.”

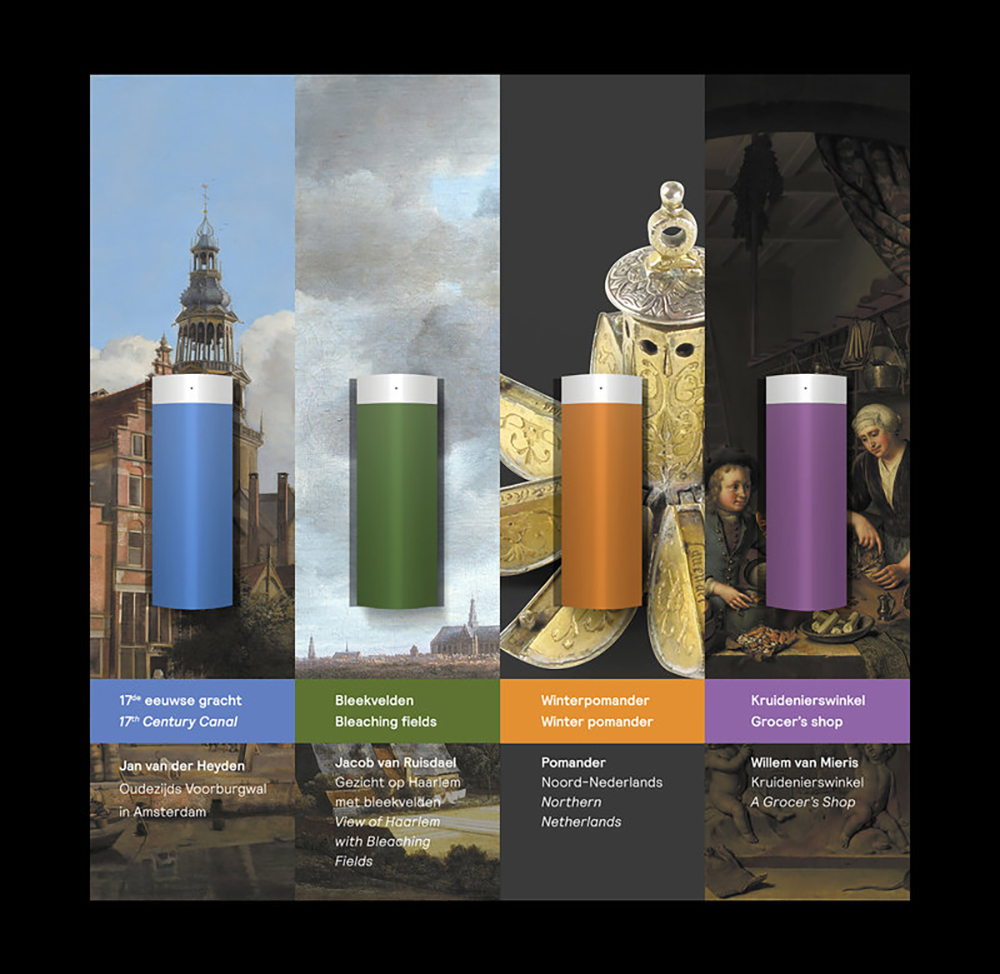

Above: Jan van der Heyden’s “View of the Oudezijds Voorburgwal with the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam,” one of the works on display at Scents in Colour. Image: Mauritshuis, The Hague; Below: The Scents in Colour fragrance range. Image: Mauritshuis.

Because museums are still closed in Holland, the Mauritshuis also created a unique “fragrance box,” available for purchase from its web shop, to coincide with a filmed digital tour of Scents in Colour. The “see-and-smell” tour, featuring van Suchtelen and Dutch culinary journalist Joel Broekaert as guides, is augmented by a suite of at-home scent bottles that coincide with four of the exhibited paintings, including Jacob van Ruisdael’s “View of Haarlem with Bleaching Fields” and Willem van Mieris’ “A Grocer’s Shop.”

It’s this scent-based intimacy, whether at home or within the Mauritshuis, that really drives the show home. “At the heart of this entire exhibition is the idea that if you can use more of your senses, the experience is more intense,” says van Suchtelen. “It allows the viewer to make a connection not only to the artwork, but also to the past — this idea of ‘historical sensation,’ that you are able to touch history.”

Van Suchtelen underscores how important smell can be in creating a full, empathic relationship with artistic subjects across time. “These Dutch 17th century daily life scenes already bring out that sense with people, but smell helps people think about perception, think about how we view the world, and how artists could reference smell both consciously and suggestively in their works. Because smell makes such a direct connection to our emotional system, you can really change the way people encounter the art.”