“Let’s imagine a world where the Benin Bronzes were never looted,” proposes Chidirim Nwaubani. In such a world, Nigeria might figure as a key cultural center, to which visitors from across the globe might flock to view its royal and sacred artifacts that bear evocative craftsmanship dating back to the 13th century. It’s activity that would stimulate the African continent’s economy, if not bolster the local creative community. But we don’t live here: despite ongoing repatriations, Nigeria’s cultural treasures, looted in a violent and acquisitive British invasion in 1897, remain dispersed across Western institutions, creating what Nwaubani recognizes as “not just an economic gap, but an artistic gap.”

In the face of a real world injustice, the designer has turned to the virtual plane to address a historical wrong. His medium? NFTs, of course. Late last year, Nwaubani masterminded Looty, a platform self-described as “the world’s first digital repatriation of art to the metaverse.” Very simply, the project digitizes stolen objects now sitting in museums, mints them as 1/1 NFTs, and sells them to benefit the Looty Fund, which will offer grants to emerging African artists. Its first collection arrived earlier in May on Rarible, featuring six NFTs centered on a Benin Bronze, currently held by the British Museum.

Looty’s first drop features 3D renderings of a Benin Bronze, centered on a variety of backgrounds and available as 1/1 NFTs. Images: Rarible

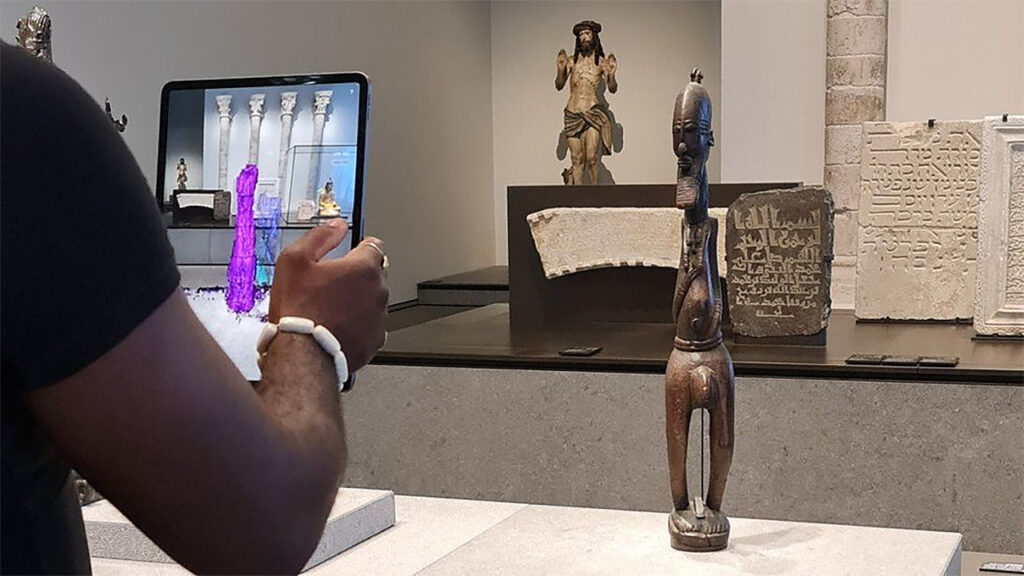

That drop, however, is the product of a larger process that Nwaubani has termed “a digital art heist.” To create its first NFTs, the Looty team physically visited the museum (in full-faced masks, no less) and used LIDAR scanning software to capture the object with pinpoint accuracy. The act ensures the initiative is working off original material, thus avoiding any copyright conflicts, while serving as an artistic intervention that digitally reclaims the artifact. “We’re entering these spaces and we’re taking back though we’re not doing it in a violent way,” he adds. “We’re owning the process.”

This form of digital repatriation — leveraging virtual assets in order to give back to its source community — echoes the Balot NFT project by the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League, bearing out how Web3 technologies, still loosely regulated, can be applied to the restitution space. Certainly, NFT-based repatriation has its limits (since it’s no replacement for physical returns), but for now, holds promise in how it might dispute IRL ownership, if not spur actual restitution.

To capture the object, the Looty team used photogrammetry and LIDAR scanning onsite at the British Museum. Image: @LootyNFT on Twitter

For Nwaubani, the realm of NFTs remains ripe with potential, considering the emerging Web3-savvy audience. “We’re moving into a space where digital assets are starting to hold more value,” he reflects. “Physical restitution is great, but for so long, it hasn’t happened. I think digital restitution is the only or the best way to go in this conversation, especially when you have institutions that are refusing to hand back items.”

For Nwaubani, the realm of NFTs remains ripe with potential, considering the emerging Web3-savvy audience. “We’re moving into a space where digital assets are starting to hold more value,” he reflects. “Physical restitution is great, but for so long, it hasn’t happened. I think digital restitution is the only or the best way to go in this conversation, especially when you have institutions that are refusing to hand back items.”

Now as then, the British Museum remains intransigent when it comes to returning its stash of Benin Bronzes, insisting it remains in “open dialogues” with Nigerian practitioners. And to be clear, Looty doesn’t intend to disrupt any ongoing repatriation processes, but more so, to “instigate and push the agenda further,” notes Nwaubani. The London institution, too, has been involved with Digital Benin, a platform that proposes to virtually reunite the objects, even as they remain in the physical possession of venues from the British Museum to the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

It’s why Looty is also gaming out a museum in the metaverse, in partnership with a Rwandan institution, which will house its Benin Bronze NFTs and upcoming drops minted of stolen artworks. “If you look at the museums that hold African artwork, we don’t have control over the narrative, the way things are displayed,” Nwaubani says. But the metaverse offers “this new space where we can create our own rules.”

Indeed, Web3 has presented the project — with its NFT drops, forthcoming metaverse museum, and Looty Fund — opportunities to accelerate the repatriation conversation on its own terms. No, it’s not a substitute for physical restitution, but in its form and format, the platform issues yet another challenge to institutional ownership, embodying a digital resistance against physical absence. “That physical gap that we’ve had,” says Nwaubani, “we can now catch up in the digital realm.”